These are the people who contributed to Black Advancement Inc. Without you, this never would have been possible. If You wish not to have your name added let Us know and you will be placed under Anonymous.

Monthly Archives: March 2011

Black People You Should Know

Richard Spikes (1878 – 1965)

Richard Spikes was born on October 2, 1878, to Monroe and Medora Spikes as the fifth of nine children. Although a capable musician on the piano and violin and despite his two of his younger brothers, Benjamin “Reb” Franklin and John Curry Spikes, would go on to become well-known jazz musician, Richard Spikes learned to cut hair in his father’s barber shop, and then became a public-school teacher in Beaumont, Texas. On October 8, 1900, Spikes married Lula B. Charlton daughter of Charles Napoleon Charlton, an ex-slave who co-founded the first public schools for Blacks in the city of Beaumont. The couple had one son, Richard Don Quixote Spikes in 1902 and moved around the southwest including Albuquerque, New Mexico and later Bisbee, Arizona where he operated a barber shop and later a saloon. While in Bisbee, Spikes became dissatisfied with how draft beer was dispensed from a keg and patented a beer-tapper (U.S. Patent number 850,070) on April 9, 1907. This beer tapper connected to a keg, the tap used tubing to ease the release of beer from the barrel, while also improving freshness over time. The patent was purchased by the Milwaukee Brewing Company and variations of the invention are still in use. This was only one of many of his inventions and patents. Although Spikes primarily interested in automobile mechanics, Spikes also sought to improve the operation of items as varied as barber chairs and trolley cars. The full list is below:

Richard Spikes was born on October 2, 1878, to Monroe and Medora Spikes as the fifth of nine children. Although a capable musician on the piano and violin and despite his two of his younger brothers, Benjamin “Reb” Franklin and John Curry Spikes, would go on to become well-known jazz musician, Richard Spikes learned to cut hair in his father’s barber shop, and then became a public-school teacher in Beaumont, Texas. On October 8, 1900, Spikes married Lula B. Charlton daughter of Charles Napoleon Charlton, an ex-slave who co-founded the first public schools for Blacks in the city of Beaumont. The couple had one son, Richard Don Quixote Spikes in 1902 and moved around the southwest including Albuquerque, New Mexico and later Bisbee, Arizona where he operated a barber shop and later a saloon. While in Bisbee, Spikes became dissatisfied with how draft beer was dispensed from a keg and patented a beer-tapper (U.S. Patent number 850,070) on April 9, 1907. This beer tapper connected to a keg, the tap used tubing to ease the release of beer from the barrel, while also improving freshness over time. The patent was purchased by the Milwaukee Brewing Company and variations of the invention are still in use. This was only one of many of his inventions and patents. Although Spikes primarily interested in automobile mechanics, Spikes also sought to improve the operation of items as varied as barber chairs and trolley cars. The full list is below:

- U.S. patent 928,813, Beer Tapper (1908)

- U.S. patent 972,277, Billiard Cue Rack (1910)

- U.S. patent 1,362,197, U.S. patent 1,362,198 Continuous contact trolley pole (1919)

- U.S. patent 1,441,383 Brake Testing Machine (1923)

- U.S. patent 1,461,988 Pantograph (1923)

- U.S. patent 1,590,557 Combination Milk Bottle Opener and Cover (1926)

- U.S. patent 1,828,753 Methods and Apparatus of Obtaining Average Samples and Temperature of Tank Liquids (1932)

- U.S. patent 1,889,814 Modifications to the automatic gear shift (1932)

- U.S. patent 1,936,996 Transmission and shifting thereof (1933)

- U.S. patent 2,517,936 Horizontally Swinging Barber’s Chair (1950)

- U.S. patent 3,015,522 Automatic Safety Brake System (1962)

Of all these innovations, the best-known are those related to automotive technology. Spikes’ gear shifting device aimed to keep the gears for various speeds in constant mesh, enhancing the turn-of-the-century invention of the automatic transmission and his automatic brake safety system is still used in some buses as a fail-safe means of stopping the vehicle to this day. Spikes is also widely credited with patenting an automobile signaling system (turn signal) in the early 1910s, though a patent record has yet to be located. Richard B. Spikes died on January 22, 1965, in Los Angeles, California at the age of 86.

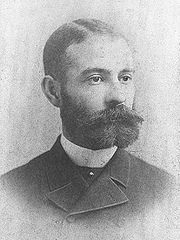

Thomas Elkins (1818 – 1900)

Dr. Thomas Elkins was born in New York State in 1818 and studied surgery and dentistry at the Albany Medical College and went on to operate a pharmacy in Albany for several decades and offered dental services as well. Beginning in the 1840s, Elkins became a member of the Albany Vigilance Committee, where Elkins served as secretary in the 1850s. As a member of the Albany Vigilance Committee, which organized to help fugitive slaves and solicited donations from citizens and was a key part of the Underground Railroad. Elkins worked with Stephen Myers (former slave) and his wife, who helped to provide all manner of assistance from food to legal aid, to medical attention to those seeking freedom and were widely considered the “best-run” Underground Railroad station in New York. They also were the publisher of the Northern Star and Freeman’s Advocate among other papers. During the Civil War, Elkins served as the medical examiner for the famed 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments. Appointed by Massachusetts’ abolitionist governor John A. Andrew, Elkins joined a group of other African Americans from Albany who volunteered for service. Following the war, Elkins travelled to Liberia, possibly as part of the Back to Africa movement. There, it was noted that he collected several “valuable seashells, minerals, and curiosities. Beginning in the 1870s, Elkins successfully filed a series of patents. On February 22, 1870, his invention (U.S. Patent number 100,020) of a table that could serve for dining, ironing and as a quilting frame, gained approval. Shortly thereafter, on January 9, 1872, he also patented the design for an improved “chamber-commode” (U.S. Patent number 122,518), a predecessor to the toilet. It combined multiple pieces of furniture into one item, and featured a bureau, mirror, bookshelf, washstand, table, easy-chair, and earth-closet or chamber-stool. Elkins’ also invented an apparatus aimed at improving refrigeration of “articles liable for decay” such as “food, or human corpses.” Approved on November 4, 1879, the device included a covered trough or container kept at low temperature by the continuous circulation of chilled water or other cooling fluid through a series of metallic coils. Keeping the bodies of the recently deceased cool posed major challenge in the 19th century, especially in cities, and Elkins’ invention was a marked improvement over other longstanding technique. In 1880, the New York Agriculture Society awarded Elkins a certificate of “highest merit” for this idea and in 1881 he was publicly recognized as the “district physician,” in The Albany Handbook, which is a position recognized by the city. Elkins died on August 10, 1900 at 82 years old having never married and no children and is buried at Albany Rural Cemetery. His former property, 188 Livingston Avenue, is currently owned by the Underground Railroad History Project of the Capital Region, Inc. They also own the Myers house and several other properties from the era.

Dr. Thomas Elkins was born in New York State in 1818 and studied surgery and dentistry at the Albany Medical College and went on to operate a pharmacy in Albany for several decades and offered dental services as well. Beginning in the 1840s, Elkins became a member of the Albany Vigilance Committee, where Elkins served as secretary in the 1850s. As a member of the Albany Vigilance Committee, which organized to help fugitive slaves and solicited donations from citizens and was a key part of the Underground Railroad. Elkins worked with Stephen Myers (former slave) and his wife, who helped to provide all manner of assistance from food to legal aid, to medical attention to those seeking freedom and were widely considered the “best-run” Underground Railroad station in New York. They also were the publisher of the Northern Star and Freeman’s Advocate among other papers. During the Civil War, Elkins served as the medical examiner for the famed 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments. Appointed by Massachusetts’ abolitionist governor John A. Andrew, Elkins joined a group of other African Americans from Albany who volunteered for service. Following the war, Elkins travelled to Liberia, possibly as part of the Back to Africa movement. There, it was noted that he collected several “valuable seashells, minerals, and curiosities. Beginning in the 1870s, Elkins successfully filed a series of patents. On February 22, 1870, his invention (U.S. Patent number 100,020) of a table that could serve for dining, ironing and as a quilting frame, gained approval. Shortly thereafter, on January 9, 1872, he also patented the design for an improved “chamber-commode” (U.S. Patent number 122,518), a predecessor to the toilet. It combined multiple pieces of furniture into one item, and featured a bureau, mirror, bookshelf, washstand, table, easy-chair, and earth-closet or chamber-stool. Elkins’ also invented an apparatus aimed at improving refrigeration of “articles liable for decay” such as “food, or human corpses.” Approved on November 4, 1879, the device included a covered trough or container kept at low temperature by the continuous circulation of chilled water or other cooling fluid through a series of metallic coils. Keeping the bodies of the recently deceased cool posed major challenge in the 19th century, especially in cities, and Elkins’ invention was a marked improvement over other longstanding technique. In 1880, the New York Agriculture Society awarded Elkins a certificate of “highest merit” for this idea and in 1881 he was publicly recognized as the “district physician,” in The Albany Handbook, which is a position recognized by the city. Elkins died on August 10, 1900 at 82 years old having never married and no children and is buried at Albany Rural Cemetery. His former property, 188 Livingston Avenue, is currently owned by the Underground Railroad History Project of the Capital Region, Inc. They also own the Myers house and several other properties from the era.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/elkins-thomas-1818-1900/ & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Elkins

Marie Van Brittan Brown (1922 – 1999)

Marie Van Brittan Brown was born in Queens, New York, on October 22, 1922. Marie married Albert Brown and they lived at 151–158 & 135th Avenue in Jamaica, Queens, New York and had two children, Albert Jr. and Norma. Marie Brown worked as a nurse and her husband, Albert Brown, worked as an electronics technician leading to both Marie and Albert working irregular hours and often work hours that did not overlap. This would leave Marie alone in her home at night in neighborhood with a very high crime rate and an often-delayed police response time. These circumstances spurred Brown to invent the first home security system at the age of 40. When Marie and her husband first came up with their security system, their invention consisted of four peepholes, a sliding camera, TV monitors, and microphones. Three peepholes were placed on the front door at different height levels; the top for tall persons, the bottom for children, and the middle for average height. The cameras could go from peephole to peephole and were connected to the TV monitors inside her home to see exactly who was at her door without having to open it. The microphones were used to talk with whoever was outside, again without having to open the door. The final element was an alarm button that could be pressed to contact the police immediately. On August 1, 1966, Marie and her husband submitted a patent application for her invention under the title, “Home Security System Utilizing Television Surveillance.” It would be the first patent of its kind, and it later influenced modern home security systems that are still used today. The patent was granted by the government on December 2, 1969, and Brown’s invention gained her well-deserved recognition, including an award from the National Scientists Committee officially making her a part of “an elite group of Black inventors and scientists.” Brown was interviewed by The New York Times four days later and was quoted saying “a woman alone could set off an alarm immediately by pressing a button, or if the system were installed in a doctor’s office, it might prevent holdups by drug addicts.” Although the system was originally intended for domestic uses, many businesses began to adopt Brown’s system given its efficacy. Through inventing the security system, Brown also invented the first closed circuit television security system and the fame of Brown’s device also led to the more prevalent CCTV surveillance in public areas. Marie Van Brittan Brown died on February 2, 1999, at the age of 76 in Jamaica, Queens, New York. Unfortunately, Marie van Brittan Brown died before she could see the new innovations added to her invention. Her initial idea allowed people to build upon it and revolutionized the entire security system and all security brands such as ADT, Ring, and more all have her to thank for her initial idea. Her invention was cited in at least 32 future patent applications. The home security business is expected to be at least a $1.5B business and is expected to triple by 2024. Norma followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a nurse and inventor. She had success in the innovative field as well as her mother, as she had over 10 inventions.

Marie Van Brittan Brown was born in Queens, New York, on October 22, 1922. Marie married Albert Brown and they lived at 151–158 & 135th Avenue in Jamaica, Queens, New York and had two children, Albert Jr. and Norma. Marie Brown worked as a nurse and her husband, Albert Brown, worked as an electronics technician leading to both Marie and Albert working irregular hours and often work hours that did not overlap. This would leave Marie alone in her home at night in neighborhood with a very high crime rate and an often-delayed police response time. These circumstances spurred Brown to invent the first home security system at the age of 40. When Marie and her husband first came up with their security system, their invention consisted of four peepholes, a sliding camera, TV monitors, and microphones. Three peepholes were placed on the front door at different height levels; the top for tall persons, the bottom for children, and the middle for average height. The cameras could go from peephole to peephole and were connected to the TV monitors inside her home to see exactly who was at her door without having to open it. The microphones were used to talk with whoever was outside, again without having to open the door. The final element was an alarm button that could be pressed to contact the police immediately. On August 1, 1966, Marie and her husband submitted a patent application for her invention under the title, “Home Security System Utilizing Television Surveillance.” It would be the first patent of its kind, and it later influenced modern home security systems that are still used today. The patent was granted by the government on December 2, 1969, and Brown’s invention gained her well-deserved recognition, including an award from the National Scientists Committee officially making her a part of “an elite group of Black inventors and scientists.” Brown was interviewed by The New York Times four days later and was quoted saying “a woman alone could set off an alarm immediately by pressing a button, or if the system were installed in a doctor’s office, it might prevent holdups by drug addicts.” Although the system was originally intended for domestic uses, many businesses began to adopt Brown’s system given its efficacy. Through inventing the security system, Brown also invented the first closed circuit television security system and the fame of Brown’s device also led to the more prevalent CCTV surveillance in public areas. Marie Van Brittan Brown died on February 2, 1999, at the age of 76 in Jamaica, Queens, New York. Unfortunately, Marie van Brittan Brown died before she could see the new innovations added to her invention. Her initial idea allowed people to build upon it and revolutionized the entire security system and all security brands such as ADT, Ring, and more all have her to thank for her initial idea. Her invention was cited in at least 32 future patent applications. The home security business is expected to be at least a $1.5B business and is expected to triple by 2024. Norma followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a nurse and inventor. She had success in the innovative field as well as her mother, as she had over 10 inventions.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-marie-van-brittan-1922-1999/ & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Van_Brittan_Brown

Samuel R. Scottron (1841[43] – 1908)

It is unclear if Scottron was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania or New England in the years 1841 or 1843. Samuel Scottron moved with his family to New York City in 1849, where he completed grammar school at the age of fourteen. During the American Civil War, he went to work for his father as a sutler for the 3rd United States Colored Infantry and almost went bankrupt. To recoup his fortunes, he moved to Florida in 1864 to operate grocery stores in Gainesville, Jacksonville, Lakeville, Palatka, and Tallahassee. While in Florida, Samuel Scottron married Anna Maria Willett in 1863 and would have five/six children together. He soon sold off his profits and relocated to work as a barber in Springfield, Massachusetts where he developed and patented his first invention, the “Scottron Mirror”. He came up with the idea after taking note of the difficulty his customers had, trying to see the back of their heads. He obtained a patent for the Scottron Mirror in March 1868. After moving to Brooklyn, New York, Scottron graduated from Cooper Union with a degree in Superior Ability in Algebra and Engineering in 1875 and belonged to the Brooklyn Academy of Sciences and the Cooper Union Alumni Society. He also would work as a traveling salesman for an import-export business located in lower Manhattan while continuing to patent his inventions and, by the late 1880s, was able to support himself and his family by manufacturing the products derived from his patents. His company, the Scottron Manufacturing Company, was located at 98 Monroe Street in Brooklyn. Scottron would then go on to obtain a patent for an adjustable window cornice in 1880, the Cornice in 1883, the Pole Tip in 1886, the Curtain Rod in 1892, and the Supporting Bracket in 1893. Many of his inventions were not patented, but he still gained royalties for them. Scottron is also credited with inventing the “leather hand strap device” used for support when standing on trolley cars. He came up with the idea after traveling to San Francisco, California. While in New York, He was a community leader, setting up organizations to promote racial harmony and fairness, as well as a public speaker and writer on race relations. Scottron spent thirty-five years writing on race-related matters for various newspapers and magazines. His articles could be found in the New York Age, the Boston Herald, and the Colored American. His final works were published in “New York African Society for Mutual Relief- Ninety Seventh Anniversary,” in 1905. In 1894, Scottron was appointed to the Brooklyn Board of Education and served as its only Black member for the next eight years and founded the Society of the Sons of New York. He would go on to become a leader in the Republican Party, where he fought for the end of slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico by serving as Chairman of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee with abolitionist Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. He held membership in the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite (33rd degree Mason) and was Grand Secretary General of its Supreme Council of the United States for several years. Scottron died of natural causes on October 14, 1908. His great granddaughter was actress and singer Lena Horne and the family life was documented by Horne’s daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, in The Hornes: An American Family.

It is unclear if Scottron was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania or New England in the years 1841 or 1843. Samuel Scottron moved with his family to New York City in 1849, where he completed grammar school at the age of fourteen. During the American Civil War, he went to work for his father as a sutler for the 3rd United States Colored Infantry and almost went bankrupt. To recoup his fortunes, he moved to Florida in 1864 to operate grocery stores in Gainesville, Jacksonville, Lakeville, Palatka, and Tallahassee. While in Florida, Samuel Scottron married Anna Maria Willett in 1863 and would have five/six children together. He soon sold off his profits and relocated to work as a barber in Springfield, Massachusetts where he developed and patented his first invention, the “Scottron Mirror”. He came up with the idea after taking note of the difficulty his customers had, trying to see the back of their heads. He obtained a patent for the Scottron Mirror in March 1868. After moving to Brooklyn, New York, Scottron graduated from Cooper Union with a degree in Superior Ability in Algebra and Engineering in 1875 and belonged to the Brooklyn Academy of Sciences and the Cooper Union Alumni Society. He also would work as a traveling salesman for an import-export business located in lower Manhattan while continuing to patent his inventions and, by the late 1880s, was able to support himself and his family by manufacturing the products derived from his patents. His company, the Scottron Manufacturing Company, was located at 98 Monroe Street in Brooklyn. Scottron would then go on to obtain a patent for an adjustable window cornice in 1880, the Cornice in 1883, the Pole Tip in 1886, the Curtain Rod in 1892, and the Supporting Bracket in 1893. Many of his inventions were not patented, but he still gained royalties for them. Scottron is also credited with inventing the “leather hand strap device” used for support when standing on trolley cars. He came up with the idea after traveling to San Francisco, California. While in New York, He was a community leader, setting up organizations to promote racial harmony and fairness, as well as a public speaker and writer on race relations. Scottron spent thirty-five years writing on race-related matters for various newspapers and magazines. His articles could be found in the New York Age, the Boston Herald, and the Colored American. His final works were published in “New York African Society for Mutual Relief- Ninety Seventh Anniversary,” in 1905. In 1894, Scottron was appointed to the Brooklyn Board of Education and served as its only Black member for the next eight years and founded the Society of the Sons of New York. He would go on to become a leader in the Republican Party, where he fought for the end of slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico by serving as Chairman of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee with abolitionist Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. He held membership in the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite (33rd degree Mason) and was Grand Secretary General of its Supreme Council of the United States for several years. Scottron died of natural causes on October 14, 1908. His great granddaughter was actress and singer Lena Horne and the family life was documented by Horne’s daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, in The Hornes: An American Family.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/scrottron-samuel-raymond-1843-1905/& https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_R._Scottron

Olivia J. Hooker (1915–2018)

Olivia J. Hooker was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma, to Samuel Hooker and Anita Hooker (née Stigger) in 1915. The family was living in the Greenwood District of Tulsa on May 31, 1921, when a group of white men carrying torches entered their home and began destroying their belongings, including her sister’s piano and her father’s record player. “It was a horrifying thing for a little girl who’s only six years old,” she told Radio Diaries in 2018. The attack was part of the Tulsa race riots of May 31–June 1, 1921, in which members of the Ku Klux Klan and other white residents of Tulsa destroyed the Greenwood District—also known as Black Wall Street for the concentration of Black-owned businesses in the area—killing as many as 300 people and leaving more than 10,000 homeless. Hooker and her family moved to Columbus, Ohio, after the riots. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in 1937 from The Ohio State University, where she also became a member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, taught third grade, and advocated for Black women to be admitted to the U.S. Navy. She applied to the Navy’s Waves (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) program but was rejected because she was black. She disputed the rejection and due to a technicality and was accepted; however, Hooker petitioned the Coast Guard instead, and in 1945, became the first Black woman to join the U.S. Coast Guard’s women’s reserve. On March 9, 1945, she was sent to basic training for six weeks in Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York. Throughout training, Hooker became a Coast Guard Women’s Reserve Semper Paratus Always Ready (SPARS). Hooker was one of only five Black females to first enlist in the SPARS program. After basic training, Hooker specialized in the yeoman rate and remained at boot camp for an additional nine weeks before heading to Boston where she performed administrative duties and earned the rank of Yeoman Second Class in the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve. In June 1946, the SPAR program was disbanded and Hooker earned the rank of petty officer 2nd class and a Good Conduct Award. In 1947, she used her GI Bill to enrolled in Columbia University’s Psychology Department where she received a M.A. degree in Psychological Services. In 1961 she received her PhD in clinical psychology from the University of Rochester, with her dissertation on the learning abilities of children with Down syndrome. With an expertise in developmental and intellectual disabilities, Dr. Hooker went on to help found the American Psychological Association’s Division 33, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and was later honored by the Association for her work with children. She served as an early director of the Kennedy Child Study Center in New York City where she gave evaluations, extra help, and support/therapy to children with learning disabilities and delays and worked the mentally disabled in women’s prisons and as a senior clinical lecturer at Fordham University in 1963. She formally retired in 1987 after a distinguished career but continued to be active in civic life. In 1997, Hooker and other survivors of the massacre founded the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, to investigate the massacre and its aftermath, and seek reparations. In 2003, she was one of the plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit filed against the state of Oklahoma and the city of Tulsa by more than 100 survivors and about 300 descendants of people who were seeking reparations for the Tulsa Massacre that took so many lives and her family home and business. The U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the case without comment in 2005. Dr. Hooker was one of the last known survivors of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre. Hooker received the American Psychological Association Presidential Citation in 2011. In 2012, she was inducted into the New York State Senate Veterans’ Hall of Fame. In 2015, setting aside the tradition of recognizing members posthumously, the Coast Guard renamed the dining facility the Olivia Hooker Dining Facility. A training facility at the Coast Guard’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. was also named after her that same year. Dr. Hooker then decided to join the Coast Guard Auxiliary in Yonkers, New York at age 95. Dr. Olivia Juliette Hooker died of natural causes at her home in White Plains, NY, on November 21, 2018, at age 103. Dr. Hooker was an active participant in the White Plains/Greenburgh NAACP until the time of her death. Tulsa Girl, by Shameen Anthanio-Williams, is a book focused on Hooker’s experiences in the Tulsa Race riots. In October 2019, it was announced that the fast response cutter USCGC Olivia Hooker would be named in her honor. This will be the sixty-first Sentinel-class cutter, due to be delivered to the Coast Guard after 2023.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hooker-olivia-j-1915/ & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olivia_Hooker

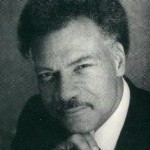

Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941)

Dr. Ernest Everett Just was born on August 14, 1883, in Charleston, South Carolina, to Charles Frazier and Mary Matthews Just. Just was only four years old when his father, died in 1887. Due to mounting debt, his mother moved from Charleston to James Island, a Gullah community off the coast of South Carolina, to work in its phosphate mines. Mary Just became a highly respected leader of the community and convinced a number of residents on the island to purchase land and start their own community. The residents renamed the community Maryville in her honor. Known as an intelligent and inquisitive student, Just was sent to attend the high school of the Colored Normal Industrial, Agricultural & Mechanical College (later named South Carolina State University) in 1996 and would later go on to Kimball Union Academy in New Hampshire and excelled in social activities and academics. After graduation from Kimball Union, Just entered Dartmouth College in 1903, where he was selected as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and graduated magna cum laude in biology with a minor in history, receiving honors in botany, sociology and history in 1907. He was also elected to the prestigious honor society Phi Beta Kappa. Just’s accepted a position at Howard University as a teacher and by 1910, he joined the Department of Biology and was appointed professor in 1912. He also would become one of the founding members of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity in 1911 at Howard while also becoming a member of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity. Omega Psi Phi was the first black Greek-lettered fraternal organization founded at a historically Black university. Just worked in research at Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts and furthered his education by obtaining a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Chicago, where he studied experimental embryology and graduated magna cum laude. He earned a doctorate in zoology in 1916 and published 50 scientific papers such as the 1924 publication “General Cytology,” which he co-authored with respected scientists from Princeton University, the University of Chicago, the National Academy of Sciences and the Marine Biological Laboratory, and two influential books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Mammals (1922) and Biology of the Cell Surface (1939). Just also served as editor of three scholarly periodicals and won the NAACP’s first Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement by a Black American. From 1920 to 1931, he was a Julius Rosenwald Fellow in Biology of the National Research Council — a position that provided him the chance to work in Europe when racial discrimination hindered his opportunities in the United States becoming one of the first Blacks to receive worldwide recognition as a scientist. Just would go on to conduct his research first in Naples, Italy, then in 1930, becoming the first American to be invited to conduct research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, Germany. His research was interrupted when the Nazis took control of Germany in 1933, forcing Just to relocated to Paris, France to continue his research. Due to his work, Just would have long absences from his wife and three kids leading to their divorce in 1939. That same year, Just married Maid Hedwig Schnetzler, a German national philosophy student he had met in Berlin. Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, France when the Nazis invaded the country and imprisoned him, holding Just in a POW camp. With the help of his wife’s father and the U.S. State Department, Just was released and brought back to the United States in 1940. Just had been ill for months prior to his detainment, but his condition deteriorated during his imprisonment. Just died on October 27, 1941, in Washington, D.C., shortly after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and was buried at the Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland at 58 years old. Dr. Ernest Everett Just was best known for being a biologist and educator who pioneered many areas on the physiology of development, including fertilization, experimental parthenogenesis, hydration, cell division, dehydration in living cells and ultraviolet carcinogenic radiation effects on cells. Held in high esteem within his field, notable Black scientist Charles Drew called Just “a biologist of unusual skill and the greatest of our original thinkers in the field.”

Dr. Ernest Everett Just was born on August 14, 1883, in Charleston, South Carolina, to Charles Frazier and Mary Matthews Just. Just was only four years old when his father, died in 1887. Due to mounting debt, his mother moved from Charleston to James Island, a Gullah community off the coast of South Carolina, to work in its phosphate mines. Mary Just became a highly respected leader of the community and convinced a number of residents on the island to purchase land and start their own community. The residents renamed the community Maryville in her honor. Known as an intelligent and inquisitive student, Just was sent to attend the high school of the Colored Normal Industrial, Agricultural & Mechanical College (later named South Carolina State University) in 1996 and would later go on to Kimball Union Academy in New Hampshire and excelled in social activities and academics. After graduation from Kimball Union, Just entered Dartmouth College in 1903, where he was selected as a Rufus Choate scholar for two years and graduated magna cum laude in biology with a minor in history, receiving honors in botany, sociology and history in 1907. He was also elected to the prestigious honor society Phi Beta Kappa. Just’s accepted a position at Howard University as a teacher and by 1910, he joined the Department of Biology and was appointed professor in 1912. He also would become one of the founding members of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity in 1911 at Howard while also becoming a member of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity. Omega Psi Phi was the first black Greek-lettered fraternal organization founded at a historically Black university. Just worked in research at Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts and furthered his education by obtaining a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Chicago, where he studied experimental embryology and graduated magna cum laude. He earned a doctorate in zoology in 1916 and published 50 scientific papers such as the 1924 publication “General Cytology,” which he co-authored with respected scientists from Princeton University, the University of Chicago, the National Academy of Sciences and the Marine Biological Laboratory, and two influential books, Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Mammals (1922) and Biology of the Cell Surface (1939). Just also served as editor of three scholarly periodicals and won the NAACP’s first Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement by a Black American. From 1920 to 1931, he was a Julius Rosenwald Fellow in Biology of the National Research Council — a position that provided him the chance to work in Europe when racial discrimination hindered his opportunities in the United States becoming one of the first Blacks to receive worldwide recognition as a scientist. Just would go on to conduct his research first in Naples, Italy, then in 1930, becoming the first American to be invited to conduct research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, Germany. His research was interrupted when the Nazis took control of Germany in 1933, forcing Just to relocated to Paris, France to continue his research. Due to his work, Just would have long absences from his wife and three kids leading to their divorce in 1939. That same year, Just married Maid Hedwig Schnetzler, a German national philosophy student he had met in Berlin. Just was working at the Station Biologique in Roscoff, France when the Nazis invaded the country and imprisoned him, holding Just in a POW camp. With the help of his wife’s father and the U.S. State Department, Just was released and brought back to the United States in 1940. Just had been ill for months prior to his detainment, but his condition deteriorated during his imprisonment. Just died on October 27, 1941, in Washington, D.C., shortly after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and was buried at the Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland at 58 years old. Dr. Ernest Everett Just was best known for being a biologist and educator who pioneered many areas on the physiology of development, including fertilization, experimental parthenogenesis, hydration, cell division, dehydration in living cells and ultraviolet carcinogenic radiation effects on cells. Held in high esteem within his field, notable Black scientist Charles Drew called Just “a biologist of unusual skill and the greatest of our original thinkers in the field.”

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/just-ernest-everett-1883-1941/& https://www.biography.com/scientists/ernest-everett-just

Minnie Buckingham Harper (1886–1978)

Minnie Buckingham was born in Winfield, West Virginia. She later moved to Keystone in McDowell County and married Ebenezer. Howard Harper, who was elected to the legislature in 1926. When Harper died in the middle of his term, the county Republican executive committee unanimously recommended Minnie to replace him and was appointed by Governor Howard M. Gore to the West Virginia House of Delegates to fill the vacancy left by the death of her husband. Harper would replace her deceased husband and became the first Black woman legislator in the United States in 1928 in the West Virginia state legislature. Her appointment reflected both the growing importance of women in American politics and the large voting bloc of Blacks in southern West Virginia. During her one session in the legislature, she served on the House committees on Federal Relations, Railroads, and Labor. Harper did not seek reelection at the end of her term. Minnie Buckingham Harper eventually moved back to Putnam County and she died in Winfield in 1978 at age 91. It would take 22 more years before another Black woman would be elected to the legislature in West Virginia.

Minnie Buckingham was born in Winfield, West Virginia. She later moved to Keystone in McDowell County and married Ebenezer. Howard Harper, who was elected to the legislature in 1926. When Harper died in the middle of his term, the county Republican executive committee unanimously recommended Minnie to replace him and was appointed by Governor Howard M. Gore to the West Virginia House of Delegates to fill the vacancy left by the death of her husband. Harper would replace her deceased husband and became the first Black woman legislator in the United States in 1928 in the West Virginia state legislature. Her appointment reflected both the growing importance of women in American politics and the large voting bloc of Blacks in southern West Virginia. During her one session in the legislature, she served on the House committees on Federal Relations, Railroads, and Labor. Harper did not seek reelection at the end of her term. Minnie Buckingham Harper eventually moved back to Putnam County and she died in Winfield in 1978 at age 91. It would take 22 more years before another Black woman would be elected to the legislature in West Virginia.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minnie_Buckingham_Harper & https://wvpublic.org/may-15-1886-west-virginias-first-african-american-female-legislator-born-in-putnam-co/

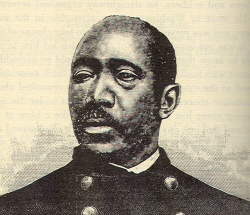

Absalom Boston (1785–1855)

Absalom Boston was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts, to Seneca Boston, a Black ex-slave father, and Thankful Micah, a Wampanoag Indian mother and was a third generation Nantucketer. Boston spent his early years working in the whaling industry. By the time he reached 20, he acquired enough money to purchase property in Nantucket. Ten years later, he obtained a license to open and operate a public inn and by 1822, At age 37 became the first Black United States mariner to captain a whaleship, Industry, manned entirely with a Black crew. The six-month journey yielded 70 barrels of whale oil and the entire crew returned intact. Boston would retire from the sea after the Industry returned to Nantucket from its historic voyage and turned his attention to civil rights and becoming a pillar of the Nantucket Black community. He established the African Meeting House in Nantucket and the African School, was a founding trustee of Nantucket’s African Baptist Society, operated a store in Newtown for the remainder of his life, and also ran for public office. When the all-white high school refused to educate his daughter, he put together a lawsuit against the Nantucket municipal government to integrate the public education system with fellow captain, Edward Pompey. By 1845, he had won the lawsuit leading to Nantucket having integrated their public schools in over 100 years before Brown v. Board of Education. Marrying three times, his sons who lived to adulthood followed him into the whaling industry. By the time Boston died in 1855, he was a respected community leader, wealthy landowner, and tireless advocate for cooperative race relations between Nantucketers and was widely considered “perhaps the wealthiest black on Nantucket.”

This information was derived from the internet @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absalom_Boston & https://www.sailmagazine.com/cruising/sail-black-history-month-series-absalom-boston & https://www.facebook.com/101064053268025/posts/a-third-generation-nantucketer-captain-absalom-boston-was-a-pillar-of-the-nantuc/5568591989848510/

Anna Julia Cooper (1858–1964)

Cooper was the daughter of a slave woman and her white slaveholder (or his brother) in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1858. After Emancipation, in 1868 she enrolled in the newly established Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute (now Saint Augustine’s University), a school for freed slaves. She quickly distinguished herself as an excellent student, and, in addition to her studies, she began teaching mathematics part-time at age 10. While enrolled at Saint Augustine’s, she realized that her male classmates were encouraged to study a more rigorous curriculum than were the female students. This realization motivated Cooper to a life advocating for the education of black women. In 1877 Anna married her classmate George Cooper, who died two years later. After her husband’s death, Cooper enrolled in Oberlin College in Ohio, along with a small group Black educators and leaders. At Oberlin, she had to protest to be allowed into the “Gentlemen’s classes” but she persevered and graduated in 1884 with a B.S. in mathematics and received a master’s degree in mathematics in 1888. In 1887 she was recruited for a job teaching in Washington, D.C. and became a teacher at the most prestigious secondary school for Blacks in the country called M Street High School,(now Dunbar High School). There she taught mathematics, science, and, later, Latin. During the 1890s Cooper became involved in the black women’s club movement and helped to unite hundreds of local and state groups into the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). The NACWC would go on to be the longest standing black civic organization in the United States. Cooper also became a popular public speaker addressing a wide variety of groups, including the National Conference of Colored Women in 1895 and the first Pan-African Conference in 1900. In 1892 Cooper published her most well-known work, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South. In it she identified how systems of oppression and domination converge around issues of race, class and gender and argued for the central place of black women in the battle for civil rights. In 1902 Cooper was named principal of the M Street High School. As principal, she enhanced the academic reputation of the school, and under her tenure several M Street graduates were admitted to Ivy League schools. The District of Columbia Board of Education refused to renew her contract for the 1905–06 school year (reason related to racism) but would return In 1910 as a teacher at M Street where she stayed until 1930. From 1911 through 1925, Cooper began studying part-time for a doctoral degree until age 67 when she became only the fourth Black woman in the US to earn her PhD, when she completed and defended her dissertation at the University of Paris, Sorbonne, which subject matter was slavery, written in French, and published in English as Slavery and the French Revolutionists, 1788–1805. From 1930 to 1941 she served as president of the Frelinghuysen University for working adults in Washington, D.C. starting at age 72 and continued to serve as the school’s registrar until well into her 90s. Cooper died in her sleep at age 105 in 1964 and is buried next to her husband in Raleigh City (VA) Cemetery. Cooper reared two foster children and five adoptive children during her lifetime as well.

Cooper was the daughter of a slave woman and her white slaveholder (or his brother) in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1858. After Emancipation, in 1868 she enrolled in the newly established Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute (now Saint Augustine’s University), a school for freed slaves. She quickly distinguished herself as an excellent student, and, in addition to her studies, she began teaching mathematics part-time at age 10. While enrolled at Saint Augustine’s, she realized that her male classmates were encouraged to study a more rigorous curriculum than were the female students. This realization motivated Cooper to a life advocating for the education of black women. In 1877 Anna married her classmate George Cooper, who died two years later. After her husband’s death, Cooper enrolled in Oberlin College in Ohio, along with a small group Black educators and leaders. At Oberlin, she had to protest to be allowed into the “Gentlemen’s classes” but she persevered and graduated in 1884 with a B.S. in mathematics and received a master’s degree in mathematics in 1888. In 1887 she was recruited for a job teaching in Washington, D.C. and became a teacher at the most prestigious secondary school for Blacks in the country called M Street High School,(now Dunbar High School). There she taught mathematics, science, and, later, Latin. During the 1890s Cooper became involved in the black women’s club movement and helped to unite hundreds of local and state groups into the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). The NACWC would go on to be the longest standing black civic organization in the United States. Cooper also became a popular public speaker addressing a wide variety of groups, including the National Conference of Colored Women in 1895 and the first Pan-African Conference in 1900. In 1892 Cooper published her most well-known work, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South. In it she identified how systems of oppression and domination converge around issues of race, class and gender and argued for the central place of black women in the battle for civil rights. In 1902 Cooper was named principal of the M Street High School. As principal, she enhanced the academic reputation of the school, and under her tenure several M Street graduates were admitted to Ivy League schools. The District of Columbia Board of Education refused to renew her contract for the 1905–06 school year (reason related to racism) but would return In 1910 as a teacher at M Street where she stayed until 1930. From 1911 through 1925, Cooper began studying part-time for a doctoral degree until age 67 when she became only the fourth Black woman in the US to earn her PhD, when she completed and defended her dissertation at the University of Paris, Sorbonne, which subject matter was slavery, written in French, and published in English as Slavery and the French Revolutionists, 1788–1805. From 1930 to 1941 she served as president of the Frelinghuysen University for working adults in Washington, D.C. starting at age 72 and continued to serve as the school’s registrar until well into her 90s. Cooper died in her sleep at age 105 in 1964 and is buried next to her husband in Raleigh City (VA) Cemetery. Cooper reared two foster children and five adoptive children during her lifetime as well.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://douglassday.org/cooper/ & https://www.britannica.com/biography/Anna-Julia-Cooper

John Jr. Mitchell (1863–1929)

John Mitchell Jr. was born on July 11, 1863 near Richmond, Virginia. The Mitchell’s were slaves and John was the first of two sons. After the Civil War, the Mitchell family moved to Richmond, and despite being free his parents continued to work for their enslavers the Lyons family. Taught how to read by his mother, Mitchell would excel academically, studying at the Richmond Colored Normal School, a high school that specialized in training Black teachers, where he would go on to graduate in 1881 as the valedictorian of his class. He began teaching at Fredericksburg Colored School and returned to Richmond to teach at the Valley School in 1883, but in 1884 the newly appointed Democratic school board fired him and 10 other Black teachers. In 1883 the Black lawyer Edwin Archer Randolph founded the Richmond Planet and Mitchell led a group of former teachers to work there. By December 1884, Mitchell became editor of the weekly Richmond Planet and soon achieved greater success and gained national prominence for its role as a promoter of civil rights, racial justice, and racial pride. Mitchell investigated lynchings, advised blacks to arm themselves in self-defense, and editorialized against the Spanish-American war, saying it would make Cubans and Filipinos subject to the racism that dominated the South. Mitchell also served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1888 (served through 1896), on the Richmond City Council, and was president of the Afro-American Press Association from 1890-1894. In 1891 he secured $20,000 for the construction of new Black schools and three years later helped persuade the city to provide enough funds to construct an armory for the First Battalion Virginia Volunteers, a black militia regiment, in Jackson Ward. Although Mitchell would run for office in 1900, the election was stained with ballot rigging against all the Black candidates. This was one of many features beginning to take hold in Virginia following the years of Reconstruction and ushering in the Jim Crow era. When Virginia authorized transit companies to begin segregating streetcars in 1904, Mitchell led a protests and organized a boycott of the streetcars. Mitchell, along with civil rights activist and entrepreneur Maggie Lena Walker, called for Blacks to “stay off the street-cars,” launching a two-year boycott of Richmond’s streetcar system. Even though the Virginia Passenger and Power Company went out of business later in 1904 the boycott was unsuccessful. In 1906 the General Assembly passed a law that mandated segregation on public transportation. The boycott dwindled out in 1906, but Mitchell nonetheless continued to abstain from riding segregated streetcars. In the 1880s, Mitchell joined the Grand United Order of True Reformers, a beneficial association established by William Washington Browne to provide life insurance for Blacks. After Browne opened the True Reformers’ bank in 1889, Mitchell sat on its board of directors, serving for five years. His success there led to his establishment of the Mechanics Savings Bank, for which he received a charter in 1901. As its president, Mitchell became a member of the predominately white American Bankers Association. Beginning in 1919, its deposits hit an all-time high of over half a million dollars then Mitchell and his bank suffered a series of economic setbacks due to post–World War I economy taking a downward turn. His troubled relationship with the White regulators and financial problems caused the Mechanics Savings Bank to close in 1922. A jury found Mitchell guilty of fraud and theft in the bank’s collapse, which were later overturned yet still impacted Mitchells political and editorial influence. In defiance, Mitchell would run for political office in 1921 for governor on the “Lily Black” Republican ticket. Mitchell scarcely campaigned at all and received only 5,036 votes out of more than 210,000 cast. Despite the triumphs and successes of his life, Mitchell died of kidney disease in poverty at his Richmond home on December 3, 1929 at 66. Although Mitchell had established Woodland Cemetery in 1917, he was buried next to his mother in Evergreen Cemetery. In June 1996 the Richmond chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists honored Mitchell with the George Mason Award, acknowledging Mitchell’s contribution to freedom of the press.

John Mitchell Jr. was born on July 11, 1863 near Richmond, Virginia. The Mitchell’s were slaves and John was the first of two sons. After the Civil War, the Mitchell family moved to Richmond, and despite being free his parents continued to work for their enslavers the Lyons family. Taught how to read by his mother, Mitchell would excel academically, studying at the Richmond Colored Normal School, a high school that specialized in training Black teachers, where he would go on to graduate in 1881 as the valedictorian of his class. He began teaching at Fredericksburg Colored School and returned to Richmond to teach at the Valley School in 1883, but in 1884 the newly appointed Democratic school board fired him and 10 other Black teachers. In 1883 the Black lawyer Edwin Archer Randolph founded the Richmond Planet and Mitchell led a group of former teachers to work there. By December 1884, Mitchell became editor of the weekly Richmond Planet and soon achieved greater success and gained national prominence for its role as a promoter of civil rights, racial justice, and racial pride. Mitchell investigated lynchings, advised blacks to arm themselves in self-defense, and editorialized against the Spanish-American war, saying it would make Cubans and Filipinos subject to the racism that dominated the South. Mitchell also served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1888 (served through 1896), on the Richmond City Council, and was president of the Afro-American Press Association from 1890-1894. In 1891 he secured $20,000 for the construction of new Black schools and three years later helped persuade the city to provide enough funds to construct an armory for the First Battalion Virginia Volunteers, a black militia regiment, in Jackson Ward. Although Mitchell would run for office in 1900, the election was stained with ballot rigging against all the Black candidates. This was one of many features beginning to take hold in Virginia following the years of Reconstruction and ushering in the Jim Crow era. When Virginia authorized transit companies to begin segregating streetcars in 1904, Mitchell led a protests and organized a boycott of the streetcars. Mitchell, along with civil rights activist and entrepreneur Maggie Lena Walker, called for Blacks to “stay off the street-cars,” launching a two-year boycott of Richmond’s streetcar system. Even though the Virginia Passenger and Power Company went out of business later in 1904 the boycott was unsuccessful. In 1906 the General Assembly passed a law that mandated segregation on public transportation. The boycott dwindled out in 1906, but Mitchell nonetheless continued to abstain from riding segregated streetcars. In the 1880s, Mitchell joined the Grand United Order of True Reformers, a beneficial association established by William Washington Browne to provide life insurance for Blacks. After Browne opened the True Reformers’ bank in 1889, Mitchell sat on its board of directors, serving for five years. His success there led to his establishment of the Mechanics Savings Bank, for which he received a charter in 1901. As its president, Mitchell became a member of the predominately white American Bankers Association. Beginning in 1919, its deposits hit an all-time high of over half a million dollars then Mitchell and his bank suffered a series of economic setbacks due to post–World War I economy taking a downward turn. His troubled relationship with the White regulators and financial problems caused the Mechanics Savings Bank to close in 1922. A jury found Mitchell guilty of fraud and theft in the bank’s collapse, which were later overturned yet still impacted Mitchells political and editorial influence. In defiance, Mitchell would run for political office in 1921 for governor on the “Lily Black” Republican ticket. Mitchell scarcely campaigned at all and received only 5,036 votes out of more than 210,000 cast. Despite the triumphs and successes of his life, Mitchell died of kidney disease in poverty at his Richmond home on December 3, 1929 at 66. Although Mitchell had established Woodland Cemetery in 1917, he was buried next to his mother in Evergreen Cemetery. In June 1996 the Richmond chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists honored Mitchell with the George Mason Award, acknowledging Mitchell’s contribution to freedom of the press.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/mitchell-john-jr-1863-1929/ & https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mitchell-john-jr-1863-1929-and-richmond-planet-1883-1996/

Shalanda Young (1977 – )

Young was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and raised in Clinton, Louisiana. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Loyola University New Orleans and a Master of Health Administration from Tulane University. Young moved to Washington, D.C. around 2001, where she became a Presidential Management Fellow with the National Institutes of Health. For 14 years, Young worked as a staffer for the United States House Committee on Appropriations until she was named staff director of the committee in February 2017. As staff director on the committee, Young was involved with creating proposals related to the 2018–2019 United States federal government shutdown and the federal government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The approval of her nomination as deputy director by the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee was less bipartisan, with GOP Senators voicing concerns over her support of the removal of the Hyde amendment from the federal budget. As the nomination of Neera Tanden for OMB director faced opposition, Democrats in the Congressional Black Caucus began to consider Young for the position of OMB director, should Tanden’s nomination fail. After Tanden’s nomination for OMB director was withdrawn, the CBC and New Democrat Coalition endorsed Young with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, and Majority Whip Jim Clyburn all releasing a joint statement in support of her. Young was confirmed by the United States Senate by a vote of 63–37 to be OMB deputy, on March 23, 2021 and President Biden announced he would make Young his nominee as OMB director on November 24 after only eight months serving as acting director. The Senate confirmed Young in a 61-36 vote on March 15, 2022 to serve as the director of OMB, a position she continues to hold to this day.

Young was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and raised in Clinton, Louisiana. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Loyola University New Orleans and a Master of Health Administration from Tulane University. Young moved to Washington, D.C. around 2001, where she became a Presidential Management Fellow with the National Institutes of Health. For 14 years, Young worked as a staffer for the United States House Committee on Appropriations until she was named staff director of the committee in February 2017. As staff director on the committee, Young was involved with creating proposals related to the 2018–2019 United States federal government shutdown and the federal government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The approval of her nomination as deputy director by the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee was less bipartisan, with GOP Senators voicing concerns over her support of the removal of the Hyde amendment from the federal budget. As the nomination of Neera Tanden for OMB director faced opposition, Democrats in the Congressional Black Caucus began to consider Young for the position of OMB director, should Tanden’s nomination fail. After Tanden’s nomination for OMB director was withdrawn, the CBC and New Democrat Coalition endorsed Young with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, and Majority Whip Jim Clyburn all releasing a joint statement in support of her. Young was confirmed by the United States Senate by a vote of 63–37 to be OMB deputy, on March 23, 2021 and President Biden announced he would make Young his nominee as OMB director on November 24 after only eight months serving as acting director. The Senate confirmed Young in a 61-36 vote on March 15, 2022 to serve as the director of OMB, a position she continues to hold to this day.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shalanda_Young

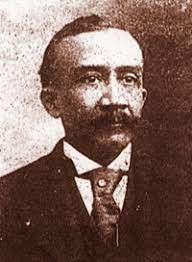

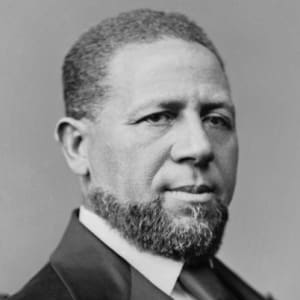

Joesph Hayne Rainey (1832 – 1887)

Joseph Rainey was born on 21 June 1832 in Georgetown, South Carolina. Rainey and his parents were enslaved, but his father was permitted to work as a barber and purchased his family’s freedom in the early 1840s. Rainey received some private schooling and took up his father’s trade in Charleston, South Carolina and would frequently travel outside of South, marrying in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1859. During the Civil War, Rainey was forced to work on the fortifications in Charleston harbor. In 1862 he escaped to Bermuda with his wife and worked there as a barber before returning to South Carolina in 1866. He returned to Charleston eager to dive into local Republican politics and was elected a delegate to the state constitutional convention in 1868 and served briefly in the state Senate before his election to the 41st Congress U.S. House of Representatives in 1870 in a special election. Rainey became the first Black American to serve in the House even though others were elected earlier but were not seated. He was appointed to the Committee on Freedmen’s Affairs and the Committee on Indian Affairs. Rainey ran for reelection in 1872 without opposition and again became the first Black American representative to preside over a house session in 1874. By 1876, the Democrats had began to re-emerge as the dominant force and Rainey barely defeated Democrat John S. Richardson for Congress for his fourth election making him the longest tenured Black person in the House during the Reconstruction era. Richardson, who never conceded the election, contested Rainey’s seat for the next two years. In 1878 Richardson won the seat, ending Rainey’s Congressional career. Rainey spent his near decade-long congressional career as an advocate for civil rights, equal protection, and an active role for the federal government in the Reconstruction of the South. In 1879 Rainey returned to South Carolina and was appointed an Internal Revenue Agent in the state by President Rutherford B. Hayes. He held the post until 1881 when he returned to Washington, D.C. where he hoped to serve as Clerk of the House of Representatives. Unable to obtain the appointment, Rainey instead started a brokerage and banking firm. After this failed he managed a coal and wood yard before returning to South Carolina impoverished and ill. Joseph Hayne Rainey died in Georgetown on August 2, 1887, leaving a widow and five children. He was 55 at the time of his death.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1800-1850/Representative-Joseph-Rainey-of-South-Carolina,-the-first-African-American-to-serve-in-the-House/ & https://www.britannica.com/biography/Joseph-Hayne-Rainey, & https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/rainey-joseph-hayne-1832-1887/

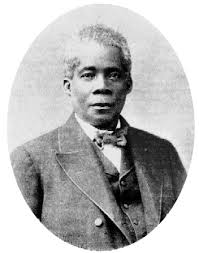

William Cooper Nell (1816 – 1874)

William C. Nell was born and raised in Boston, Massachusetts, and the son of a prominent tailor and Black activist. In the 1830s, he became politically active as a member of the Juvenile Garrison Independent Society where he wrote plays, hosted political debates, was mentored by William Lloyd Garrison, and was a printer’s apprentice for Garrison’s newspaper, the Liberator. Nell would go on to graduate with honors from the Boston’s African school. However, despite his achievements, Nell was excluded from citywide ceremonies honoring outstanding scholars because he is Black.This led Nell to a campaign to integrate Boston schools, co-authoring a petition to the Massachusetts Legislature with over 2000 signatures from the Black Boston community demanding school integration. Nell’s efforts to desegregate Boston’s schools initiated a century-long nationwide campaign which climaxed in Brown v. Board of Education (1954-55). Nell would also go on to become a founding member of the New England Freedom Association in 1842( a black Boston organization that assisted fugitive slaves in their efforts to gain freedom), campaign to desegregate the Boston railroad in 1843, the Boston performance halls in 1853, and co-founded the Massasoit Guards, a black military company in 1854. Nell moved to Rochester at the end of the 1840s, where he became the publisher of Frederick Douglass‘s newspaper, the North Star (1847). By 1850 he had returned to Boston, where he ran unsuccessfully for the Massachusetts Legislature on the Free Soil Party ticket while simultaneously working on the Underground Railroad. Nell would author the Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851) and The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855) two of the earliest histories of Black people in America. By 1861, he became the first Black American to hold a federal position as clerk in the U.S. Postal Department. In 1858, to protest the 1857 Dred Scott decision, Nell successfully organized and petitioned Boston to celebrate Crispus Attucks Day in acknowledgement of the contributions of Blacks in the Revolutionary War and to justify Black claims to full citizenship. William C. Nell died, from “paralysis of the brain,” in 1874.

William C. Nell was born and raised in Boston, Massachusetts, and the son of a prominent tailor and Black activist. In the 1830s, he became politically active as a member of the Juvenile Garrison Independent Society where he wrote plays, hosted political debates, was mentored by William Lloyd Garrison, and was a printer’s apprentice for Garrison’s newspaper, the Liberator. Nell would go on to graduate with honors from the Boston’s African school. However, despite his achievements, Nell was excluded from citywide ceremonies honoring outstanding scholars because he is Black.This led Nell to a campaign to integrate Boston schools, co-authoring a petition to the Massachusetts Legislature with over 2000 signatures from the Black Boston community demanding school integration. Nell’s efforts to desegregate Boston’s schools initiated a century-long nationwide campaign which climaxed in Brown v. Board of Education (1954-55). Nell would also go on to become a founding member of the New England Freedom Association in 1842( a black Boston organization that assisted fugitive slaves in their efforts to gain freedom), campaign to desegregate the Boston railroad in 1843, the Boston performance halls in 1853, and co-founded the Massasoit Guards, a black military company in 1854. Nell moved to Rochester at the end of the 1840s, where he became the publisher of Frederick Douglass‘s newspaper, the North Star (1847). By 1850 he had returned to Boston, where he ran unsuccessfully for the Massachusetts Legislature on the Free Soil Party ticket while simultaneously working on the Underground Railroad. Nell would author the Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851) and The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855) two of the earliest histories of Black people in America. By 1861, he became the first Black American to hold a federal position as clerk in the U.S. Postal Department. In 1858, to protest the 1857 Dred Scott decision, Nell successfully organized and petitioned Boston to celebrate Crispus Attucks Day in acknowledgement of the contributions of Blacks in the Revolutionary War and to justify Black claims to full citizenship. William C. Nell died, from “paralysis of the brain,” in 1874.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/nell-william-c-1816-1874/ & https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/nell-william-cooper

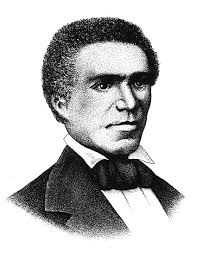

Thomas L. Jennings (1791 – 1856)

Thomas L. Jennings was born in 1791 in New York City. He started his career as a tailor and eventually opened one of New York’s leading clothing shops. Inspired by frequent requests for cleaning advice, he began researching cleaning solutions and experimenting with different solutions and cleaning agents. He tested them on various fabrics until he found the right combination to treat and clean them. He called his method “dry-scouring,” a process now known as dry cleaning. Jennings filed for a patent in 1820 and was granted a patent for the ”dry-scouring” process he had invented just a year later. The patent to Jennings generated considerable controversy during this period. Under the United States patent laws of 1793 and 1836, both enslaved and free citizens could patent their inventions(this was overturned in 1858 by the Supreme Court and was again overturned in 1870 allowing all men to have patents). Tragically, the original patent was lost in a fire, but by then, Jennings’ process of using solvents to clean clothes was well-known and widely heralded. The patent was awarded on March 3, 1821 (US Patent 3306x) for his “dry-scouring” making Jennings the first Black man to receive a patent. Jennings spent the first money he earned from his patent on legal fees to buy his family out of slavery and abolitionist activities and by 1831, became assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia. Jennings’ daughter, Elizabeth, an activist like her father, was the plaintiff in a landmark lawsuit after being thrown off a New York City streetcar while on the way to church. With support from her father, Elizabeth sued the Third Avenue Railroad Company for discrimination and won her case in 1855. The day after the verdict, the company ordered its cars desegregated. After the incident, Jennings organized a movement against racial segregation in public transit in the city; the services were provided by private companies. The same year, Jennings was one of the founders of the Legal Rights Association, a group that organized challenges to discrimination and segregation and gained legal representation to take cases to court. Thomas Jennings died in New York City in 1856.

Thomas L. Jennings was born in 1791 in New York City. He started his career as a tailor and eventually opened one of New York’s leading clothing shops. Inspired by frequent requests for cleaning advice, he began researching cleaning solutions and experimenting with different solutions and cleaning agents. He tested them on various fabrics until he found the right combination to treat and clean them. He called his method “dry-scouring,” a process now known as dry cleaning. Jennings filed for a patent in 1820 and was granted a patent for the ”dry-scouring” process he had invented just a year later. The patent to Jennings generated considerable controversy during this period. Under the United States patent laws of 1793 and 1836, both enslaved and free citizens could patent their inventions(this was overturned in 1858 by the Supreme Court and was again overturned in 1870 allowing all men to have patents). Tragically, the original patent was lost in a fire, but by then, Jennings’ process of using solvents to clean clothes was well-known and widely heralded. The patent was awarded on March 3, 1821 (US Patent 3306x) for his “dry-scouring” making Jennings the first Black man to receive a patent. Jennings spent the first money he earned from his patent on legal fees to buy his family out of slavery and abolitionist activities and by 1831, became assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia. Jennings’ daughter, Elizabeth, an activist like her father, was the plaintiff in a landmark lawsuit after being thrown off a New York City streetcar while on the way to church. With support from her father, Elizabeth sued the Third Avenue Railroad Company for discrimination and won her case in 1855. The day after the verdict, the company ordered its cars desegregated. After the incident, Jennings organized a movement against racial segregation in public transit in the city; the services were provided by private companies. The same year, Jennings was one of the founders of the Legal Rights Association, a group that organized challenges to discrimination and segregation and gained legal representation to take cases to court. Thomas Jennings died in New York City in 1856.

This information was derived from the internet @ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/jennings-thomas-l-1791-1856/ & https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_L._Jennings

Francis L. Cardoza (1837 – 1903)

Francis L. Cardoza was born on February 1,1837 to Jacob N. Cardoza, a white journalist, and a free woman of mixed African and Native American ancestry, in Charleston, South Carolina. Cardoza was apprenticed to a carpenter at age 12 and completed his apprenticeship and journeyman status by age 21, when he left to study in Great Britain. He spent four years at the University of Glasgow, and three years attending Presbyterian seminaries in Edinburgh and London. Cardoza returned to the United States in 1864 and became the pastor at the Temple Street Congregational Church in New Haven, Connecticut and married Catherine Romena Howell (had six children). He left the pulpit to concentrate on education with the American Missionary Association (AMA) and asked them to send him south to establish a school to train black teachers. In his new position, Cardoza directed an integrated staff which included white teachers from the North and black teachers from both the North and South. As southerners reclaimed property confiscated in the Civil War, Cardoza was required to find a new location for the school. In 1867 Cardoza and his teachers moved to Bull Street and renamed the school the Avery Institute based on the Avery Estates $10,000 donation. The Avery Institute became a very successful teacher education school and, later, a bastion of Charleston’s black elite. Cardoza also began his political career in 1866, when he served on a board advising the military commander of South Carolina about voter registration regulations. By 1868, he was elected to the state constitutional convention, drew up plans for state-supported public education, and served as president of the Union League, which worked to ensure a Republican victory in the elections. As the only black candidate on the state-wide Republican ticket, Cardoza was elected South Carolina’s secretary of state, becoming the first Black state official in South Carolina history, leading to his resignation from Avery Institute just before it was formally dedicated. As secretary of state, Cardoza was reelected in 1870 and fought against the fraud in the state’s Land Commission. Next, Cardoza was elected as state treasurer where he continued efforts of reform to lower taxes and eliminate corruption until 1876. In 1877 Cardoza left South Carolina, accepting a post in the U.S. Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. despite South Carolina Democrats charging him with eight counts of fraud in a smear campaign that was resolved in 1879, resulting in a pardon and dismissal of the charges. When Cardoza was done with politics, he became the principal of Washington D.C.’s Colored Preparatory High School (now known as Paul Laurence Dunbar High School) from 1884 through 1896, creating one of the country’s leading black preparatory schools and adding a two-year non-college preparatory course in business. However, due to continued criticism of Cardoza, he eventually stepped away from the school. Cardoza died on July 22, 1903.